For some reason, I like the green crackle paint job on the Chinese-made clock sitting just to my left. I don’t however, care much for what the hands are pointing to; 4:30 in the morning. I’m pulling my second and last shift on the radar, a ground surveillance doppler unit that allows us to detect enemy infiltration along the Cambodian border.

The small van that contains the operator’s end of the radar system is cramped and hot in spite of the 2 ventilation fans that are whirring away overhead. In the background I can hear chatter on the radio net, most of it official, some not. I check the target log for the night and see that a half dozen targets were detected and four were fired on. I make a mental note to scan those particular areas again during my shift.

Sweat trickles down my brow and I begin to stick to the metal folding chair. I feel very tired. I haven’t had an uninterrupted night’s sleep in 11 months. Eleven long  months of being awakened twice nearly every night for radar duty, more if our camp is attacked. Sleep during the day is almost impossible due to the sweltering heat, even if I have time for it. But, I have work to do. The generator that supplies power to the radar has accumulated a lot of hours and it demands daily maintenance. It’s near the end of it’s tour, just like me.

months of being awakened twice nearly every night for radar duty, more if our camp is attacked. Sleep during the day is almost impossible due to the sweltering heat, even if I have time for it. But, I have work to do. The generator that supplies power to the radar has accumulated a lot of hours and it demands daily maintenance. It’s near the end of it’s tour, just like me.

Uh, oh… I hear something outside. I reach for the fan switches and shut them off. I wait, and listen… gunfire, but it’s in the distance… the FSB about ¼ mile down the road. Our ARVN camp is probably OK for the moment. It’s getting unbearably hot in the van now, but I decide to leave the fans off so I can hear what’s going on outside. This is when I really feel uncomfortable being on-duty in the van; I can’t tell what’s going on around our perimeter.

I try to focus on the scope and tune my ears to the speaker attached to the radar system. Being doppler makes the TPS-25 radar unusual. It generates incredible audio sounds from moving targets. Listening to a column of enemy troops walking down a trail is surreal, almost unbelievable. Their arms and legs make distinct “whooshing” noises, a sound that I’ll never forget.

My eyes are getting tired…I struggle to make them focus. There it is… the unmistakable “grass” is moving on the left side of the scope. I move the range gate to the flicker and listen carefully. Movement! I mark the spot that the bug-light has illuminated on the map located just above the scope and then record the coordinates in the logbook. I re-position the range gate and listen again as the column passes through the gate. I estimate 8 to 10 people moving in northwesterly direction. After recording this information in the log I key the mic and report the target to TOC (tactical operations center).

About 5 minutes pass before TOC declares the target a hostile and designates a fire base to fire on it. A few more minutes pass before I hear the anticipated word, “shot!” I acknowledge and wait for the howitzer rounds to impact. The seconds tick by, …there, I see it, the tell-tale puffy flickers on the baseline of the scope. The rounds have fallen short and to the left of the target. I compute the corrections and report the new information to TOC. A couple of minutes later new rounds arrive, this time right on the mark. All movement in the area has ceased. I know there will be no movement, even if we missed. A helicopter ride to the site later today will tell. I don’t want to go… maybe it’s someone elses turn.

It’s 06:00 now, time to shutdown the radar. This night has been a good one; our camp wasn’t hit and we found some good targets. I log the shutdown, then open the van door. The relatively cool morning air feels refreshing. I walk over to the generator, throw the circuit breakers and then shut it down. I give it a little pat of affection…and give silent thanks. I dread the idea of troubleshooting a balky generator in the darkness, not to mention the wrath from headquarters if we’re not on the air. I manage a small smile to myself as I think how seldom this happens. I’m on a good team.

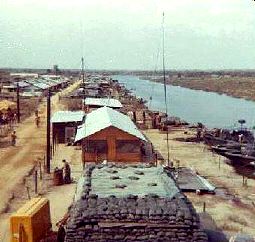

It’s getting lighter now. I gaze up at our  84 foot tower that supports the radar dome. I never get used to the orange color of the tower. It just, well, sticks out so blatantly. Why does it have to be orange? And so tall? Heck, it’s not even an original part of the radar system. I think the original 15 foot mast worked

84 foot tower that supports the radar dome. I never get used to the orange color of the tower. It just, well, sticks out so blatantly. Why does it have to be orange? And so tall? Heck, it’s not even an original part of the radar system. I think the original 15 foot mast worked  well enough — and it’s sure a lot safer. We must be crazy for climbing on the tower. No one ever talks about it but I know we all think the same thing — the tower is an enemy sniper’s dream. Yet, we all share the duties of maintaining the equipment up there. I feel a shiver of adrenaline again.

well enough — and it’s sure a lot safer. We must be crazy for climbing on the tower. No one ever talks about it but I know we all think the same thing — the tower is an enemy sniper’s dream. Yet, we all share the duties of maintaining the equipment up there. I feel a shiver of adrenaline again.

Cramps! The cramps are coming back again! I run for the can — literally a small box-like structure that sits over a 55-gallon drum that has been cut in half and filled partially with diesel fuel. Because of the odor and smoke when it’s burned off, the can is located just outside the berm, near the wire. I always feel vulnerable out there. I peer through the cracks in the walls when sitting out there — for all the good it would do, but it makes me feel a little better.

After the can session I start thinking about my next meal. Wonder what I can scrounge up. I guess the C-rations aren’t that bad but I can’t help but notice that I’ve lost weight; I’m down to 122 pounds from my normal 140. I notice that the rats are scurrying around, no doubt looking for breakfast also.

After “breakfast” I walk over to the water well and begin the task of drawing water for our shower, a 55 gallon drum mounted on a stack of ammo boxes. In the evening, all of us will enjoy the luxury of a nice shower. Well, maybe it’s a luxury; I’ve picked up a nasty case of ring-worm on my right arm and upper back. Weird stuff.

I can’t help but notice that the children of the ARVN soldiers are beginning to come out of their bunkers to play. I’m amazed at how resilient these little rascals are; inventing games, running and playing with big smiles across their faces. I share some of the candy that we get in our care packages with the kids. Of the 12 camps that we’ve been based at this is the only one that has families with the ARVN soldiers — quite unusual. I figure that they have no where else to go. I can’t imagine raising kids in such an environment.

It’s time for me to service the generator. The spark-plugs must be thoroughly cleaned and the oil changed. At 2000+ hours, the engine is now burning enough oil to foul the plugs near the  end of each 12 hour night. It won’t run through the next night without this service. I make sure there’s enough gasoline on hand for the next night. Just as I finish cleaning and servicing the generator the sky opens up and begins dumping an unbelievable amount of water on us. The rain feels good but it will turn our camp into a mud hole. The bunkers will leak and then the mildew will make its presence known in all clothing that isn’t quickly dried out. I pull the canvas cover over the generator and head into the nearby tent to sit out the storm.

end of each 12 hour night. It won’t run through the next night without this service. I make sure there’s enough gasoline on hand for the next night. Just as I finish cleaning and servicing the generator the sky opens up and begins dumping an unbelievable amount of water on us. The rain feels good but it will turn our camp into a mud hole. The bunkers will leak and then the mildew will make its presence known in all clothing that isn’t quickly dried out. I pull the canvas cover over the generator and head into the nearby tent to sit out the storm.

Inside, I look over my rifle and equipment and see that it’s time to do laundry. The storm passes and I wander out to the well again and draw some more water. I collect my uniforms and  grab the box of Tide ™ soap and head for a small cement slab near the water well. There, I find our washing machine; a green plastic tub. I pour in some water, soap, toss in a couple of pieces of clothing and then start stomping, just like making wine I think. I quit using the locals for a washing service as my uniforms were consistently returned with mildew, something I just can’t tolerate.

grab the box of Tide ™ soap and head for a small cement slab near the water well. There, I find our washing machine; a green plastic tub. I pour in some water, soap, toss in a couple of pieces of clothing and then start stomping, just like making wine I think. I quit using the locals for a washing service as my uniforms were consistently returned with mildew, something I just can’t tolerate.

After my clothes are draped over the tower guy-wires to dry, I grab my letter-writing kit and begin my second letter this week to my wife of 13 months. Lord how I miss her! First, though I re-read her last 3 letters. For a few moments my mind drifts away from here, to another world… a dream.

I’m startled back to reality as the land-line barks it’s stacatto ring. Someone else is closer and picks up the field-phone. I ignore the rest and get back to my letter writing…oops, almost forgot my short-timer’s calendar on the back of my well-worn writing tablet. Its been a few days since I X’d off any days so it feels good as I mark off 3 more. Let’s see…I only have 27 days left! I’m getting more nervous by the day just thinking about actually going home. Later today I plan to add more sandbags around my sleeping area at the end of the tent. A little more schrapnel protection never hurts, especially when you’re getting short.

Shower time. I grab a bar of Lux ™ soap from the subsistence package and head for the make-shift shower clad in only my boxer shorts and flip-flop sandals. The shower isn’t enclosed so that vulnerable feeling creeps out of it’s box again as I wash my hair. I refuse to close my eyes. I look around as I wash. I can see the tree-line a couple hundred yards away. I wonder if charlie is watching me.

I hear Judy Collins. Don, a new guy, has a brand new Akai ™ tape deck with a nifty 8-track tape player in the side. With the sun on the horizon and the air temperature subsiding to an almost tolerable level, we gather up a few sorry looking folding chairs and sit down to enjoy the music. The mosquitoes and flies are out in full-force and compete for our attention as we listen. Later in the evening we will watch Laugh In on a black and white TV, courtesy of AFVN. Truly incredible.

Before I know it my section leader, a buck Sgt., has posted the duty roster for the night. It’s a simple system; everyone advances one shift each night. Round and round it goes. The early shifts are the best as we put the radar on the air at 18:00, so the first 2 operators avoid being awakened twice during the night. Just get up once, unless our camp is getting hit.

I’m on first shift tonight. Soon enough I have the generator on-line and the radar up. First shift is pretty slack because curfew is not yet in effect and all I can do is watch the farmers come in from the rice paddies. Funny how water buffalo look and sound like 2 people on the radar. I’m sure we’ve shelled a few water buffalo in the past few months. I feel for the farmers. But, they’re supposed to keep the animals penned up at night. Not my fault.

An hour and a half later, my first shift ends. My best friend Mark has the second shift so I find him and leave him to his troubles while I find something to eat and ready for some sack time. As I sit down to munch on some C-rations our  mascot, Dog, shows up. I give him a customary cracker and he rewards me with a lick and wagging tail. Wish I could take him home with me. He sure is a good watchdog at night; good ears.

mascot, Dog, shows up. I give him a customary cracker and he rewards me with a lick and wagging tail. Wish I could take him home with me. He sure is a good watchdog at night; good ears.

Time to get some sleep. I duck under the mosquito netting that surrounds my cot and stretch out on the musty poncho liner. I start thinking about my new bride again and wonder how things are going for her back in the world. Then I wonder how my folks are doing. Soon, the distant drone of the generator fades away and I drift into a fitful sleep.

I awaken for some reason. It’s now totally dark inside the tent. I don’t move. Just carefully listen. Then it suddenly occurs  to me why I woke up; the generator isn’t running. I grab my flashlight and head for the door flap. As I walk, I keep my fingers over the end of the flashlight so only a trickle of light hits the ground. No sense making myself any more visible than necessary. Soon, I hear my buddy quietly cussing and swearing at the generator and mentioning something about empty gas barrels. Seems that he forgot to move the gas line to a full barrel during his shift. We unscrew the cap on another barrel and slip in the gas line. After a few pulls on the starter rope the generator is once again singing it’s tune. Since the radar was only down for a few minutes, nothing is said to the people back at headquarters. Why make waves? I head back to my rack, hoping I can get back to sleep before next shift. Everything fades away again.

to me why I woke up; the generator isn’t running. I grab my flashlight and head for the door flap. As I walk, I keep my fingers over the end of the flashlight so only a trickle of light hits the ground. No sense making myself any more visible than necessary. Soon, I hear my buddy quietly cussing and swearing at the generator and mentioning something about empty gas barrels. Seems that he forgot to move the gas line to a full barrel during his shift. We unscrew the cap on another barrel and slip in the gas line. After a few pulls on the starter rope the generator is once again singing it’s tune. Since the radar was only down for a few minutes, nothing is said to the people back at headquarters. Why make waves? I head back to my rack, hoping I can get back to sleep before next shift. Everything fades away again.

“Incoming!”, someone screams. In an instant I’m awake. My heart starts racing as I grope for my helmet, M-16 and flak-vest in the darkness. I hear that unmistakable whistling noise as another rocket passes overhead. A second or two later I hear the explosion. That all-too-familiar feeling of fear starts to grip me again, but I do my best to fight it off. Everyone in our tent dives for the adjacent bunker. We wait and listen in the darkness. A few minutes pass. Nothing. Quickly, we gather up our gear and head out to the berm-line and hug the sandbags, shoulder to shoulder with the infantry troops. Every few minutes I hear the noise of a hand-launched parachute flare rocketing into the sky. I always marvel at the odd, moving shadows produced by the flares as they drift slowly earth-ward. Although the flares are well away from our camp borders I can still make out dozens of soldiers manning our perimeter in the dim light. We wait and wait. It doesn’t appear that Charlie is going to initiate a ground attack tonight but extra guards are posted and the rest of us head back to find some hole to sleep in. I feel drained.

Just as I drift off to sleep again some idiot starts shaking my elbow. It’s Dale. Time for my second shift on the radar. A few minutes later I join him in the radar van. As the door closes, the interior lights automatically come back on and my eyes squint involuntarily. Dale briefs me on the evening’s activities. Charlie has been active tonight; several targets were detected and a couple of them were fired on. I note the new grease-pencil marks on the map and the log entries. Dale takes a couple of more drags on his cigarette and then heads out the door. As he leaves I can’t help but notice that he looks quite a bit older than when he first came on the team 5 months ago. I wonder how I look as I turn back to the radar console. My ball game again.

![]() of my new home kept bouncing around in my mind as I gazed at the dead, dry landscape surrounding the base. I failed to see anything that fit the name. I thought something like Fort Hot or Fort Dusty seemed more appropriate. Or maybe, Fort Bummer. Yeah, Ft. Bummer covered it pretty well. But hey, who am I to complain, now that I’m a buck-private who is given free clothing, free room and board and cheap haircuts?! On top of that, they’re actually paying me to have all this fun!

of my new home kept bouncing around in my mind as I gazed at the dead, dry landscape surrounding the base. I failed to see anything that fit the name. I thought something like Fort Hot or Fort Dusty seemed more appropriate. Or maybe, Fort Bummer. Yeah, Ft. Bummer covered it pretty well. But hey, who am I to complain, now that I’m a buck-private who is given free clothing, free room and board and cheap haircuts?! On top of that, they’re actually paying me to have all this fun!![]() formation in front of the building. Two drill sergeants were staring at us impatiently. We stood at attention, nervously waiting. Finally it came; a verbal dressing-down like I’ve never heard before. In a very colorful language the drill sergeants proceeded to tell us what they thought of us. Words such as, “scum-bags” and “maggots,” rolled off their tongues with amazing ease. And those were the more polite ones. Also, they noticed that a couple of recruits were carrying cameras, so they admonished us not to ever take a picture of a drill sergeant. If they suspected someone took a picture of them, the drill sergeant explained that they would open the camera and examine the film. If no drill sergeant pictures appeared, the camera would be closed and returned to the recruit (it seemed that some drill sergeants thought they were part-time comedians). Anyway, regardless of what the drill sergeants thought of us at the moment, the Army was about to begin an intensive 8 week training process that would transform us into real soldiers.

formation in front of the building. Two drill sergeants were staring at us impatiently. We stood at attention, nervously waiting. Finally it came; a verbal dressing-down like I’ve never heard before. In a very colorful language the drill sergeants proceeded to tell us what they thought of us. Words such as, “scum-bags” and “maggots,” rolled off their tongues with amazing ease. And those were the more polite ones. Also, they noticed that a couple of recruits were carrying cameras, so they admonished us not to ever take a picture of a drill sergeant. If they suspected someone took a picture of them, the drill sergeant explained that they would open the camera and examine the film. If no drill sergeant pictures appeared, the camera would be closed and returned to the recruit (it seemed that some drill sergeants thought they were part-time comedians). Anyway, regardless of what the drill sergeants thought of us at the moment, the Army was about to begin an intensive 8 week training process that would transform us into real soldiers. form of privacy. Every aspect is communal; showering, sleeping, relieving and whatever. The rigorous training regime certainly made it easy to sleep though, despite the sometimes noisy living quarters.

form of privacy. Every aspect is communal; showering, sleeping, relieving and whatever. The rigorous training regime certainly made it easy to sleep though, despite the sometimes noisy living quarters. unmerciful summer heat. Since most of the rifle ranges and related training facilities were located miles from our company area, we were often transported in what we called “cattle cars.” Basically, they resembled a semi-truck trailer, except the spartan interior was equipped with chromed-steel hand-holds that ran from floor to ceiling. There were no seats and very few windows. In fact, the “windows” were just small openings near the ceiling for ventilation. We were crammed into the cattle cars like sardines and despite the vents, it still got unbelievably hot inside. And since there were no real windows to look out of, the ride was usually very nauseating.

unmerciful summer heat. Since most of the rifle ranges and related training facilities were located miles from our company area, we were often transported in what we called “cattle cars.” Basically, they resembled a semi-truck trailer, except the spartan interior was equipped with chromed-steel hand-holds that ran from floor to ceiling. There were no seats and very few windows. In fact, the “windows” were just small openings near the ceiling for ventilation. We were crammed into the cattle cars like sardines and despite the vents, it still got unbelievably hot inside. And since there were no real windows to look out of, the ride was usually very nauseating. never could make up their minds about the location of the white-washed rocks bordering the flag-pole and walkways. One day we would carry all of them down to the creek bed and the next day we would bring them back and line them up perfectly where they were the day before! This might’ve had something to do with training, but I vowed to never become a drill sergeant at this point.

never could make up their minds about the location of the white-washed rocks bordering the flag-pole and walkways. One day we would carry all of them down to the creek bed and the next day we would bring them back and line them up perfectly where they were the day before! This might’ve had something to do with training, but I vowed to never become a drill sergeant at this point. ![]()

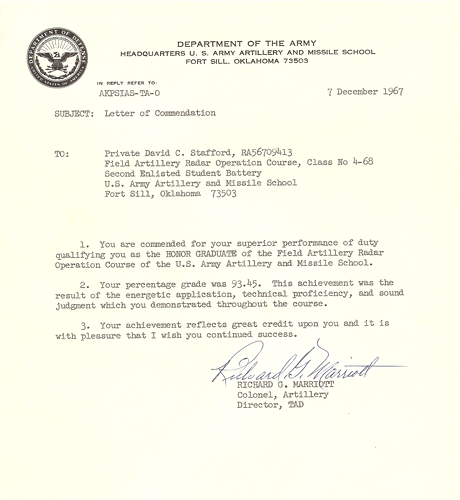

Individual Training. This was the moment of truth for draftees as the Army now assigned their MOS (Military Occupational Specialty). For many (probably most), it was on to Advanced Infantry training. The remainder were shipped off to various other schools to become cooks, mechanics, clerks, field artillery gunners, engineers, armorers, medics and a multitude of other specialties that the Army needed. Generally, enlistees chose their desired MOS at the time of enlistment so there were few surprises at their AIT assignments. Still, there were many tears shed that day, particularly for those drawing Infantry MOS’s. With the war in Vietnam building it almost guaranteed duty there. For me, it was off to Ft. Sill, Oklahoma for 8 weeks of field artillery radar training. I felt Vietnam wasn’t in the cards for me. As it turned out, I could not have been more mistaken.

Individual Training. This was the moment of truth for draftees as the Army now assigned their MOS (Military Occupational Specialty). For many (probably most), it was on to Advanced Infantry training. The remainder were shipped off to various other schools to become cooks, mechanics, clerks, field artillery gunners, engineers, armorers, medics and a multitude of other specialties that the Army needed. Generally, enlistees chose their desired MOS at the time of enlistment so there were few surprises at their AIT assignments. Still, there were many tears shed that day, particularly for those drawing Infantry MOS’s. With the war in Vietnam building it almost guaranteed duty there. For me, it was off to Ft. Sill, Oklahoma for 8 weeks of field artillery radar training. I felt Vietnam wasn’t in the cards for me. As it turned out, I could not have been more mistaken.